Body

Get to know your body through a better understanding of your anatomy and find the answers to some of your most common questions.

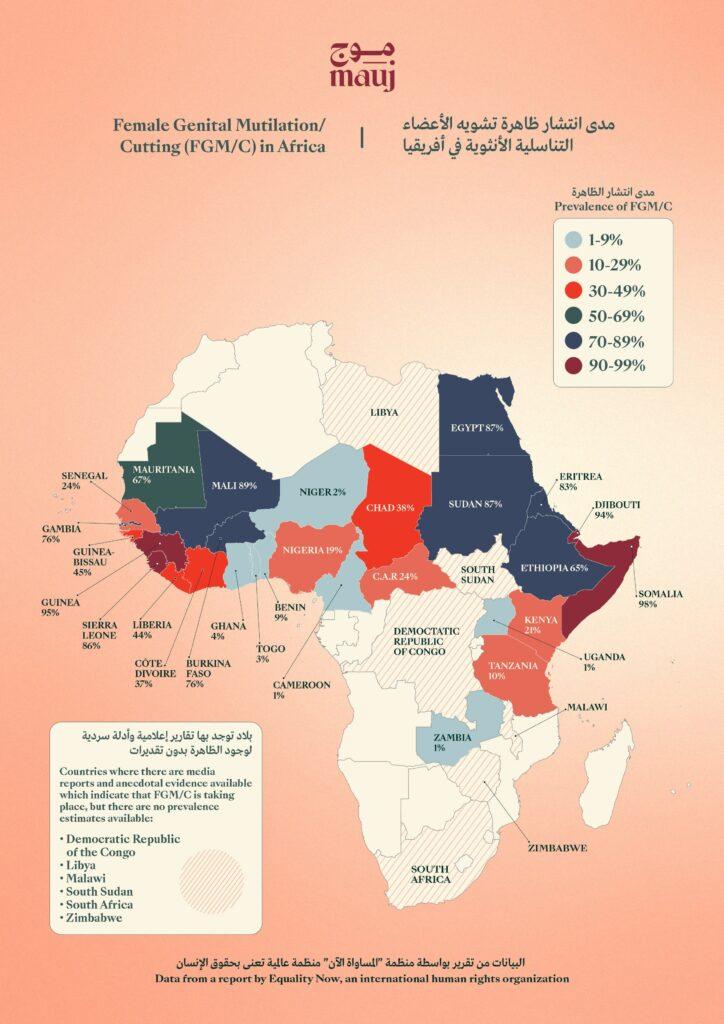

Even today, the statistics on FGM in the Arab world remain alarming, especially in Africa. This chart shows the prevalence of FGM amongst women on the continent, with Egypt and Sudan at 87% and Somalia reaching close to 98% in 2020.

Let's take a closer look at what FGM is and, more crucially, explore the reasons it's still performed on women and young girls in our communities.

Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) refers to all procedures that involve the partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or any other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons. This practice is recognized internationally as a violation of human rights, health, and the integrity of girls and women.

The World Health Organization classifies Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) into four major types, based on the extent of the procedure performed.

This entails removing the “prepuce,” the skin fold that surrounds the clitoris, as well as, in extremely rare circumstances, removing the clitoris in its entirety.

This goes further than Type I and involves the partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora, with or without excision of the labia majora (the outer vaginal lips).

This is the most severe form and is often referred to as “pharaonic circumcision.” It involves creating a covering seal to narrow the vaginal opening. This seal is formed by cutting and repositioning the labia minora or labia majora, sometimes through stitching, with or without the removal of the clitoris.

All other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes fall under this type. This includes a range of practices, such as pricking, piercing, incising, scraping, and cauterizing the genital area.

FGM carries with it a multitude of health risks that can profoundly impact women and girls not only in the immediate aftermath of the procedure but for the rest of their lives.

Initially, the procedure can lead to severe pain and excessive bleeding, which in some cases can be life-threatening. The use of non-sterile instruments increases the risk of infections and can cause urinary issues such as painful urination and urinary tract infections.

The healing process can be complicated by the formation of cysts, abscesses, and scar tissue, leading to chronic pain and discomfort.

Women who have undergone FGM are at a heightened risk of experiencing complications during childbirth, including the need for C-sections, risky deliveries, and excessive bleeding after birth.

Women who have been subjected to FGM may suffer from anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and lowered self-esteem. Their sexual health can be significantly affected, with women experiencing decreased sexual satisfaction, pain during sex, and complications in their sexual relationships.

At its core, FGM is rooted in the desire to control women’s sexuality. To this day, in some Arab societies, there exists a pervasive belief that a woman who has not undergone FGM will be unable to manage her sexual urges, therefore risking her purity and, by extension, her family’s honor. This notion is so ingrained that, in the Egyptian dialect for example, FGM is often referred to as “al-tahoor,” which translates to “purification.”

But it goes even deeper than that, as FGM evolved to become a deeply embedded cultural practice. We’ve heard from women in these communities that FGM is so ingrained that opting out is no longer a personal choice but a defiance of cultural norms. Women themselves, having been subjected to and suffered from FGM, later become proponents and perpetuate the cycle under the weight of social obligation. They fear that refusing to subject their daughters to FGM would alienate their families from the community and diminish the prospects of future marriage for their daughters.

This complex web of cultural tradition, social pressure, and the policing of women's bodies and sexuality creates a challenging environment for change. Yet, despite these challenges, there’s a rising movement to stop FGM and end the cycle of abuse.

Two women from the Mauj community, one from Sudan and another from Egypt, have graciously shared their FGM stories with us. We are privileged to pass this honor on to you. Hear their testimonials here and here.

Several NGOs and movements have been at the forefront of change, driving awareness and facilitating community dialogues. For instance, in Egypt, The National Council for Women (NCW) and the National Council for Childhood & Motherhood (NCCM) established a national FGM committee to eradicate FGM in Egypt that included governmental an non-governmental stakeholders as well as important executive, judicial, and religious authorities.

Similarly, the Saleema Initiative in Sudan aims to change societal perceptions of FGM, promoting the concept of "saleema," which signifies wholeness, in reference to girls remaining uncut.

Legal frameworks play a critical role in the battle against FGM. In recent years, countries like Sudan have made significant progress by officially criminalizing FGM in 2020. Egypt, too, has taken legal steps against FGM, with amendments to the law in 2016 increasing penalties for those performing the act.

Sadly, despite these advances, the implementation and enforcement of these laws remain challenging, and they face immense societal resistance. In some areas, FGM is still performed in secrecy, under unsanitary and unsafe conditions. This is why we need to address the root cause and work towards a major cultural shift that puts our health, safety, and rights above all else.

If you've been subjected to FGM or are unsure if you have, please know there's hope and a supportive community ready to embrace you. Reach out to us, and we'll connect you with all the resources and support available in your country.

Did you find the answer you were looking for? Is there something we missed? What did you think of this resource? We want to hear from you.